One of the things we intently study here at Mortimus is how the old power players made their mark, how they navigated the halls of power, and how they dealt with people and situations. We study them partly because these men can be quite entertaining, but also because in their story arc we can find the fodder that fuels our own agency.

Our last piece was about wargaming and the study of grand strategy, which has been the hallmark of these power players, and we’ve previously also analyzed how ideas spread and ferment in their networks of influence.

In this piece we’d like to explore the ingredients that shapes these world leaders. Sherman Kent—the father of intelligence analysis and an important figure in the history of the CIA—wrote in his 1965 classic:

“Whatever the complexities of the puzzles we strive to solve and whatever the sophisticated techniques we may use to collect the pieces and store them, there can never be a time when the thoughtful man can be supplanted as the intelligence device supreme”.

— Sherman Kent, “Strategic Intelligence for American World Power”, 2nd ed. (1965)

This was back in an era when ‘human intelligence’ was still solely the ‘intelligence device supreme’. But now things have changed. Enhanced by artificial intelligence, operators across the world are becoming more adept at their jobs, and their analysis. As models improve, and companies continue to add more applied features to them, we will no longer be the sole ‘intelligence device supreme’. The future is more likely to be hybrid — with state of the art models (or close to it) being available to the median consumer for next to nothing, enhancing their intelligence in the process.

If that happens what skillsets should we build up if we want to aspire to greatness, and remain competitive?

Peter Thiel thinks that a “long overdue rebalancing of society” is coming1. The Math People, heralded as exemplars of intelligence and genius, will be supplanted by those that are adept with words. It clearly won’t be as simple as that, and perhaps a better way to look at it is through Howard Gardner’s framework from his book “Frames of Mind”. Howard—a development psychologist from Harvard—formed his theory of multiple intelligences, which proposes the differentiation of human intelligence into eight distinct intelligences, rather than defining intelligence as a single general ability:

Linguistic Intelligence (word smart),

Logical-Mathematical Intelligence (number/reasoning smart),

Spatial Intelligence (picture smart),

Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence (body smart),

Musical Intelligence (music smart),

Interpersonal Intelligence (people smart),

Intrapersonal Intelligence (self-smart),

Naturalist intelligence (nature smart).

Current iterations of AI are enhancing the first three elements of intelligence. But it hasn’t yet made its way to interpersonal intelligence, and even its linguistic intelligence can’t match the elegance and originality of human wordsmiths.

So these models are aiding raw intelligence, which in turn enhances the significance of subtler characteristics of intelligence. Our job is to figure out what they are, and how other people have wielded them to great effect. This essay is an attempt at doing just that.

Let’s start exploring these questions with a few stories and snippets.

Before we begin, I’d love to welcome the three new people who have joined us since our last essay! We try our best to not be boring, and give you unique insights into our consilient world. For more essays subscribe here:

Signals & Gestures

Henry Kissinger was many things (diplomat, idealist, war-criminal) but he was never dull. Presidents from Kennedy to Obama have sought his advice, and he was a powerful strategic thinker who knew how to deftly navigate wiry people and knotty situations. Kissinger—the professor who became a practitioner—is worthy of study.

Our first story centres on his dealings with the Chinese. In 1969, Richard Nixon presided over the Oval Office and Kissinger was his National Security Advisor. This was a highly charged era: the Vietnam War was still ongoing and relations with both the Russians and Chinese were sour. The Americans had been trying to establish contact with the Chinese, but in light of the global situation they had to be careful; any misstep could be construed as being conciliatory to the ‘enemy’.

“Both parties had to tread warily, feeling their way toward each other with significant but tenuous messages and gestures”.2

This was around the time when the Soviet Union’s rivalry with the Chinese was increasing and China felt encircled on all sides. It needed allies, and so the top brass at the time (The Premier Chou En-Lai and Party Chairman Mao Zedong) decided to send a message. Both Chou En-Lai and Mao were adept in Chinese subtlety, and on China’s National Day Chou En-Lai led the American writer Edgar Snow and his wife to stand next to Mao and be photographed during the anniversary parade.

This was a signal. Kissinger later realized its meaning: “I came to understand that Mao intended to symbolize that American relations now had his personal attention.”

The Americans had to respond. Strong-headed Nixon went ahead and gave an interview to TIME Magazine and made strong remarks about China’s eventual role in the global order, adding: “If there is anything I want to do before I die, it is to go to China. If I don’t, I want my children to.”

The stage was slowly being set.

On October 25th, Nixon also met President Yahya Khan of Pakistan who was on his way to Beijing. Here the Americans established a secret channel via Pakistan. Nixon briefed Yahya on the points he wanted the Chinese to hear, hinted at the resumption of harmonious relations and said that the Americans were willing to send a secret emissary to Beijing for talks.

On December 8th, the Pakistani ambassador contacted Kissinger’s staff. He had a reply message from Beijing.

Ambassador Hilaly was invited to the Oval Office and presented an envelope with the message, and due to security concerns told Kissinger to write its contents down as he dictated them. Here’s how Kissinger describes the encounter:

“We were so preoccupied with this mechanical chore that we did not notice the incongruity of this elegant spokesman of the elite of a country based on an ancient religion dictating a communication from the leader of a militant Asiatic revolutionary nation to a representative of the leader of the Western capitalist world; or the phenomenon that in an age of instantaneous communication we had returned to the diplomatic methods of the previous century—the handwritten note delivered by messenger and read aloud. An event of fundamental importance took place in a pedantic, almost pedestrian, fashion.”

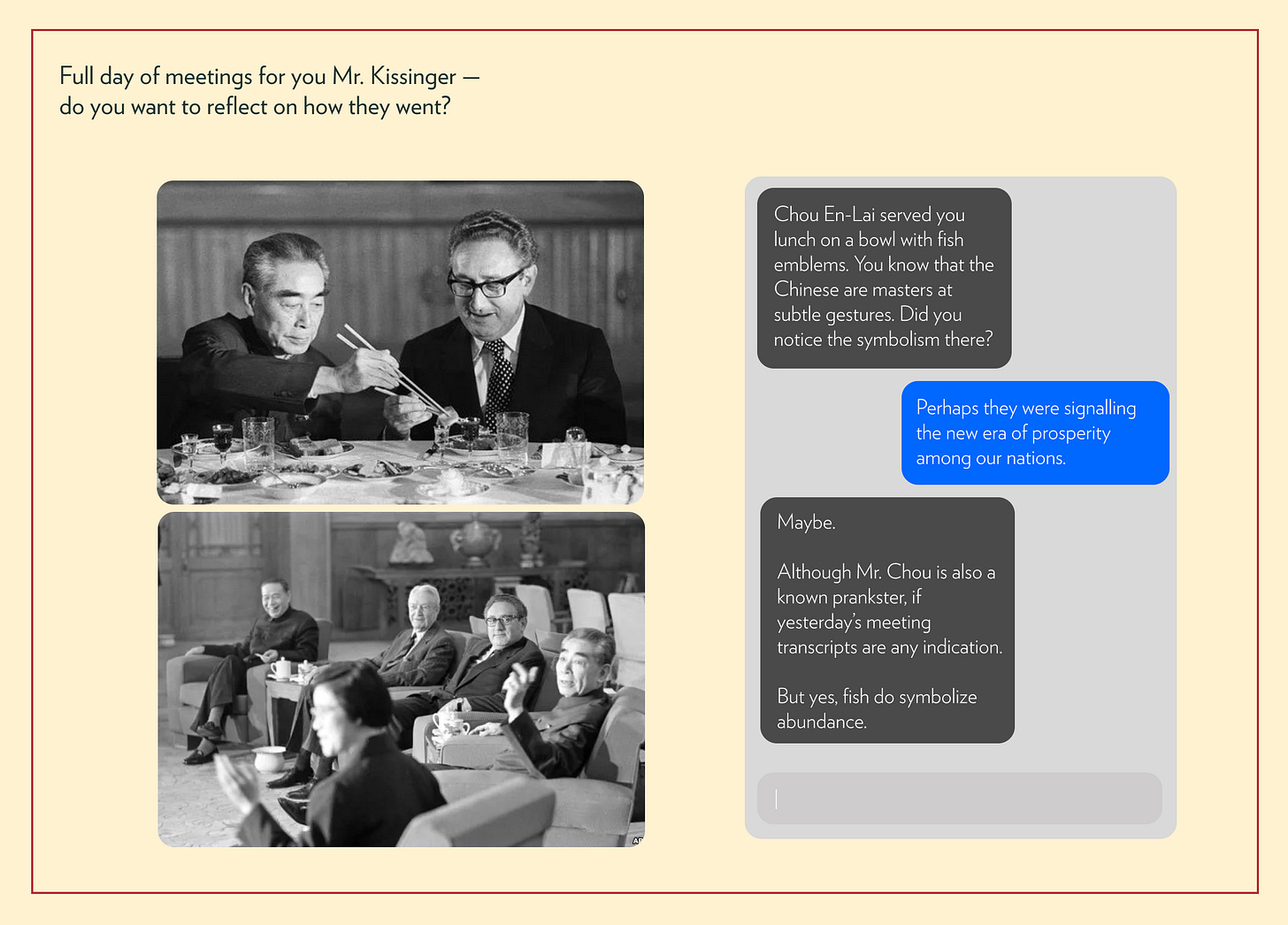

Nixon eventually decided to send Kissinger as the emissary. Kissinger understood U.S. policy the best and was very familiar with the ‘complicated’ President to be able to pave a way for his eventual visit. So on July 9th, with help from the Pakistanis, Kissinger arrived in Beijing to greet Premier Chou En-Lai.

“Chou En-lai arrived at 4:30. His gaunt, expressive face was dominated by piercing eyes, conveying a mixture of intensity and repose, of wariness and calm self-confidence. He wore an immaculately tailored gray Mao tunic, at once simple and elegant. He moved gracefully and with dignity, filling a room not by his physical dominance (as did Mao or de Gaulle) but by his air of controlled tension, steely discipline, and self-control, as if he were a coiled spring. He conveyed an easy casualness, which, however, did not deceive the careful observer. The quick smile, the comprehending expression that made clear he understood English even without translation, the palpable alertness, were clearly the features of a man who had had burned into him by a searing half-century the vital importance of self-possession. I greeted him at the door of the guest house and ostentatiously stuck out my hand. Chou gave me a quick smile and took it. It was the first step in putting the legacy of the past behind us.”3

Throughout the next few years, Kissinger spent many hours with Chou En-Lai, engaged in long-discussions and talks that cemented their relationship and “[gave] shape to the intangibles of mutual understanding”. These were two ideological enemies being frank with each other, building a structure for future relationships. Kissinger was open in his judgement of Chou, he had “no illusions about the system Chou represented” and considered him a formidable foe and a fascinating interlocutor:

“Chou En-lai, in short, was one of the two or three most impressive men I have ever met. Urbane, infinitely patient, extraordinarily intelligent, subtle, he moved through our discussions with an easy grace that penetrated to the essence of our new relationship as if there were no sensible alternative.”

Kissinger respected this stalwart in a way only diplomats could. Their exchanges opened the way for Nixon’s historic visit to China in 1972 and laid the foundation upon which modern-day Sino–U.S. relations are built.

Psychological Terrain & Databases of Folklore

Now let’s step away from the world of high-politics, and into the world of speculative fiction.

For the second story we’d like to focus on a few snippets from Neal Stephenson’s 1995 bestseller: “The Diamond Age”.

We discovered Stephenson in our late teens through Goodreads book lists titled “Science Fiction and Fantasy Must Reads” and “Nerdventure” (we were impressionable kids), and have been hooked ever since. He’s a wonderful storyteller, weaving complex stories featuring a plethora of scientific and technical advancements and sprinkling them with his wicked humour. Basically, he’s our favourite kind of consilient writer.

Set in Shanghai in a nanomaterial-abundant future, The Diamond Age centres around a piece of technology called “A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer”. The Primer is an advanced machine that resembles a book found in an antiquarian bookstore, but its pages are etched with computational machinery that allows itself to adapt to its reader’s environment and teach them to become better versions of themselves.

This device is designed by the nano-tech engineer John Percival Hackworth, a thoughtful inventor who wants a better future for his daughter Fiona. He wants her to be successful: “Starting your own company and making it successful was the only way. Hackworth had thought about it from time to time, but he hadn't done it. He wasn't sure why not; he had plenty of good ideas…And he'd met a few big lords, spent considerable time with Lord Finkle-McGraw developing Runcible, and seen that they weren't really smarter than he. The difference lay in personality, not in native intelligence.”

Hackworth kept pondering over basic questions of education: “How could he inculcate her with the nobleman's emotional stance—the pluck to take risks with her life, to found a company, perhaps found several of them even after the first efforts had failed?”. Maybe there’s a device that can train her personality…

Hackworth finds a Lord (a local elite) who commissions this Primer for his granddaughter. On delivery to him, Hackworth explains how the Primer works, imprinting the child’s voice and memory into its database, after which “it will see all events and persons in relation to that girl, using her as a datum from which to chart a psychological terrain, as it were. Maintenance of that terrain is one of the book's primary processes. Whenever the child uses the book, then, it will perform a sort of dynamic mapping from the database onto her particular terrain.”

The Lord is fascinated with this explanation. He asks Hackworth if this is like a database of folklore. Hackworth replies that it works at a more nuanced level:

“Folklore consists of certain universal ideas that have been mapped onto local cultures. For example, many cultures have a Trickster figure, so the Trickster may be deemed a universal; but he appears in different guises, each appropriate to a particular culture's environment.”

“As technology became more important, the Trickster underwent a shift in character and became the god of crafts—of technology, if you will—while retaining the underlying roguish qualities. So we have the Sumerian Enki, the Greek Prometheus and Hermes, Norse Loki, and so on.

“In any case, the Trickster/Technologist is just one of the universals. The database is full of them. It's a catalogue of the collective unconscious.”

The Primer tracks the environment and reactions of the reader and uses its database to guide the reader towards a certain personality archetype—“mapping the universals onto the unique psychological terrain of [a] child”.

In Praise of Intelligence

Suppose that we too had access to a ‘database of universals’ from which to iteratively study. What would that look like? What elements would we focus on?

We’ve written before about having an Internal Council—using the lives of a few key builders and thinkers to guide our own intelligence. We can augment this council (our ‘personal board of directors’) with members of different archetypes: the Tinkerer, the Diplomat, the Soldier, the Merchant, the Astronaut, the Spy.

Plutarch basically built such a database when he wrote The Parallel Lives, his portraits of the Greek and Roman generals and statesmen. As Alex Petkas reminds us in his excellent Cost of Glory podcast4, Plutarch intended for these biographies to be primarily read as moral (not historical) tales. Leaders across generations have read this stories to enhance their intelligence, to form their worldviews.

Can we build a tool that incorporates the nuances in these tales into its own database, and then eventually help us map them onto our psychological terrain?

We don’t think such a tool exists yet.

For your final consideration we’d like to present a few choice descriptions of intelligence from some of our recent readings:

“Behind the well-mannered finish he was as tough as nails, as bright as the evening star, and no man’s fool.” — Richard Rhodes on E.O. Wilson

“Promethean intellect triumphant.” — E.O. Wilson on J. Robert Oppenheimer5

“Alan was a great wizard. No one understood what he said, but he said it in such a way that everybody bought it…He was thoughtful, careful, measured, not at all impulsive…” — Arthur Levitt on Alan Greenspan6

Can a tool capture the complexity of this kind of intelligence? Can it imprint this on us? Not quite.

We may have to do this work ourselves.

Becoming a Centaur

Here’s the central question we began with: How do we craft our own intelligence? How do we stay ahead of machines that have ingested the world’s information?7

We can start by noticing how the old masters did it, and then augment their approach.

Let’s unwind the stories above.

Nothing beats raw work. When Kissinger was about to meet his Chinese counterparts, he prepared meticulously. “The negotiator should know not only the technical side of the subject but its nuances. He must above all have a clear conception of his objectives and the routes to reach them. He must study the psychology and purposes of his opposite number and determine whether and how to reconcile them with his own.” The briefing papers that he and his team prepared were revised countless times until they couldn’t be revised anymore, and this exercise sharpened Kissinger’s thinking.

But if we consider this sort of work to be manual (albeit necessary), the true work was in the small, thoughtful considerations: understanding the Chinese signals, responding in kind, liaising with third-parties like Pakistan, and then once the meeting took place: actually sizing up a formidable figure like Chou En-Lai and building those ‘intangibles of mutual understanding’.

Perhaps the raw work of collecting information and building the briefs could be handled by AI tools. But the analysis? Thoughtful analysis? That’s the domain of a sharp mind—and it can be improved.

When Sherman Kent described the ‘thoughtful man’ as the intelligent device supreme, he had a very specific vision in mind. To Kent, men of intelligence had a sacred duty: to safeguard the national welfare. As part of their duty they had to upgrade themselves, to own the stature of being the ‘intelligent device supreme’.

We too have this same duty.

“…no matter whether done instinctively or with skillful conscious mental effort intelligence work is in essence nothing more than the search for the single best answer.”8

This essay has an ulterior motive. It’s our attempt at brainstorming how we can build Hackworth’s Primer for ourselves. By digging into stories like those of Kissinger, we’re trying to see what made people like him noteworthy, and to eventually train those characteristics in ourselves. To build our own internal database of universals.

There’s a lot of manual work involved in building such a thing, but we’d like to brainstorm the seed for an early prototype.

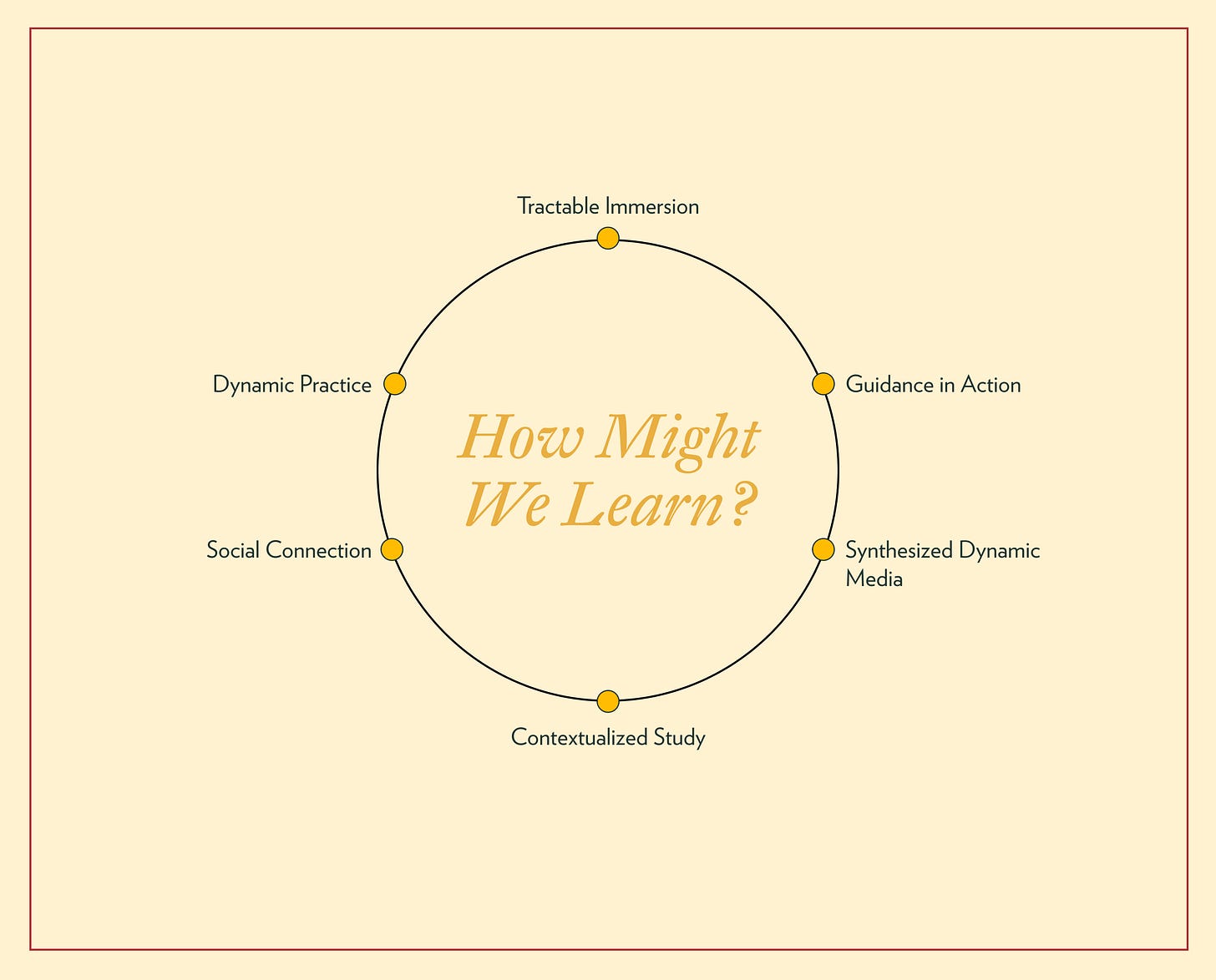

Recently,

gave a talk at UC San Diego on the topic of learning9. Andy’s an applied researcher, focused on building ‘transformative tools for thought’— interfaces that expand what people can think, do and learn. In his talk, he explores what an ideal learning environment looks like and outlines six of its elements:Andy demoes how an AI agent with contextual awareness can enhance our learning, guiding us into the right directions: “[it] can learn from every piece of text that’s ever crossed [the user]’s screen, every action they’ve taken on the computer. It can synthesize scaffolded dynamic media, so that [the user] can learn by doing, but with guidance.”

We think the basics of Andy’s system can be used to teach us both explicit and subtle intelligence.

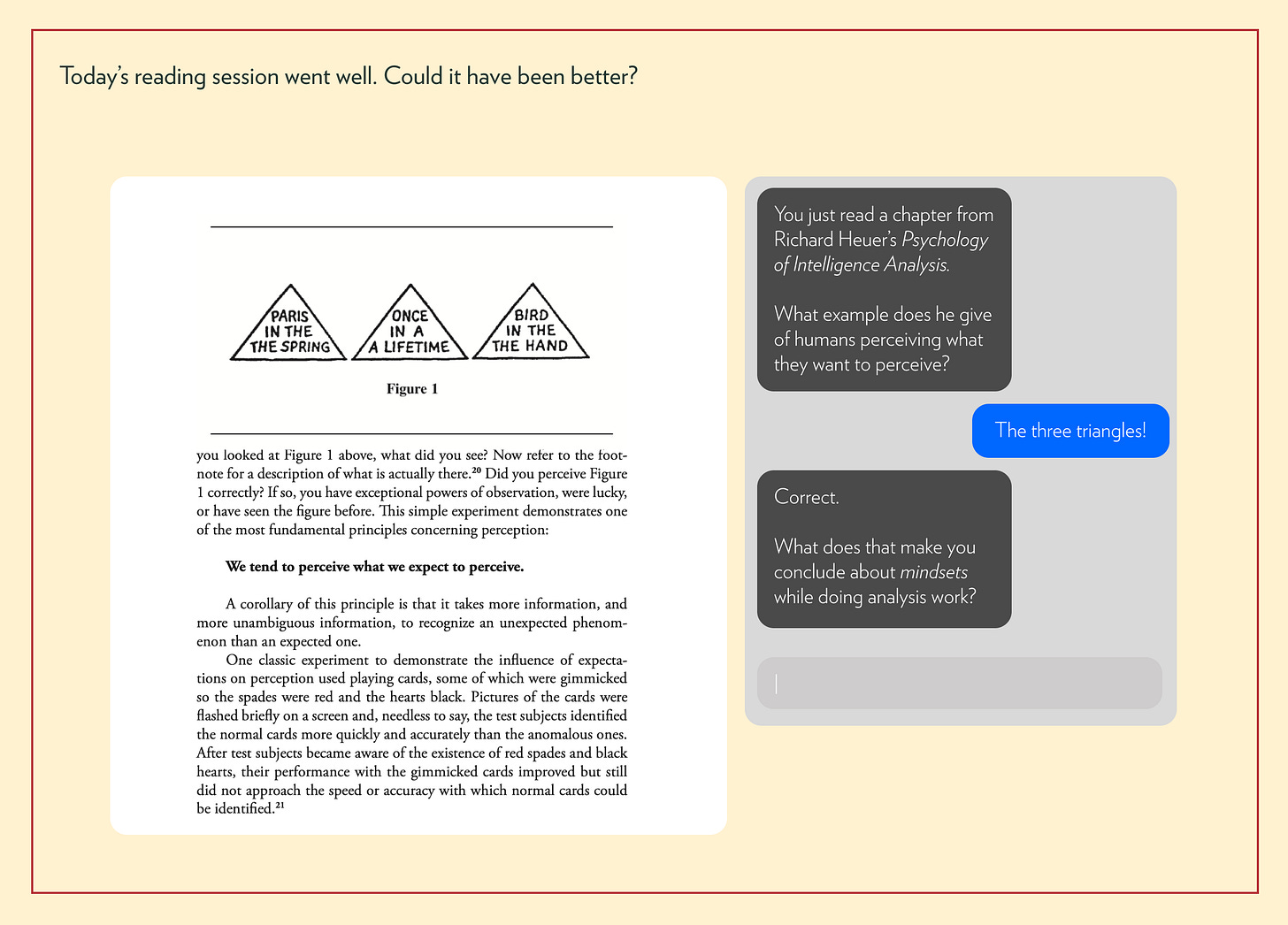

For example, say we want to improve our general analysis skills. After scouring many syllabi and talking to skilled leaders we realize that the best book for the job is Richard Heuer’s Psychology of Intelligence Analysis. It is a relatively short (albeit dense) book that is freely available from the CIA’s website, so it can be read fairly easily.

But to enhance our reading, what if we augmented the book?

A tool opens up on your OS and notices you reading. After you finish a chapter, a context window pops up and starts asking you questions. The questions are formed naturally, based on your current progress, and answers that you provide. Plus, these questions are not static — they actively force you to make connections.

This same approach can also work for face to face meetings.

Disclaimer: this part is more in the realm of science fiction for now, but we can see tools like these developing eventually. All the data we gather as we interact with others (meeting videos, transcripts, notes, briefings), all these are rich sources of context. If the models are tuned to the right specifications (i.e. they know what cognitive bias looks like in action, and can actively cross question your assumptions) then this can be a formidable tool.

Such a tool may not turn us into the sharp men of yesteryear, but continuous practice with them may get us closer.

Isn’t that worth trying?

We hope this brainstorm serves as a viable seed from which useful tools can germinate—and turn us into intelligent centaurs10.

Onwards to Consilience!

Kissinger, “White House Years” (Chapter 18: An Invitation to Peking)

Kissinger, “White House Years” (Chapter 19: The Journey to Peking, “The Middle Kingdom: First Meeting with Chou En-lai”)

This is like the Founders podcast, but for ancient Greco-Roman leaders. Worth checking out.

These two quotes are from Richard Rhodes’ biography of E.O. Wilson “Scientist”.

“Assuming a human can read 300 words a min and 8 hours of reading time a day, they would read over a 30,000 to 50,000 books in their lifetime. Most people would manage perhaps a meagre subset of that, at best 1% of it. That’s at best 1 GB of data.

LLMs on the other hand, have imbibed everything on the internet and much else besides, hundreds of billions of words across all domains and disciplines.”

Sherman Kent “Strategic Intelligence for American World Power”, 2nd ed. (1965)

Matuschak, A. (2024, May 8). How might we learn?. UCSD Design@Large. https://andymatuschak.org/hmwl

Nicky Case’s essay “How to become a Centaur”, sheds light on the term centaur. We use it to refer to a tech-augmented human.