The Grand Strategy Dilemma

and how Wargaming sessions can be an answer.

Recently, Lux Capital announced the official public launch of their ‘Riskgaming’ Initiative—a series of strategy games that will help decision-makers navigate the complexity of our world. Think of them as elevated case-studies, where instead of reading about them as a third-party, you actively participate as a key decision maker in their evolving scenarios.

Wargaming has an established history in military studies. For the past two hundred years, wargames have been used to prepare strategists to deal with specific battle scenarios and coordinate evolving defence/offence situations.

The modern version of wargames can trace their origins to Kriegsspiel, a game first invented by the Prussian war councillor Baron Leopold von Reisswitz in the 1800s. Reisswitz created a table-top game that depicted a scaled version of actual terrain and had blocks painted in regimental colors to depict fighting units. A game-master assisted opposing teams in determining progress on the battlefield by consulting complex tables, with dice rolls used to account for uncertainties in the battle. However, this innovation was merely used to instruct princes in warfare—and regular armies did not use it at all1.

Now, the story is different. Wargames have been used as a tool to support decision makers and leaders dealing with complex interrelated phenomena. Even though their use is still mostly limited to military settings, there is a future where wargaming can go beyond the defence setting, and the people at Lux agree:

While the word “war” is present, that’s really a synonym for competition, and we believe that wargaming should expand far beyond the remit of defense. How will synthetic biology and the CRISPR economy change the organization of American healthcare? How do public schools compete with the prevalence of homeschooling in an era of social distrust? How will emerging markets compete in industries that require large capital outlays like semiconductors?

—Feb 2023. Danny Crichton. “Lux Riskgaming Initiative”

That’s a grand ambition, something that we at Mortimus would love to see. However, we have our questions. Will this new style of wargaming only be used by select decision makers? Or will their use proliferate among a wider array of people: students, employees, junior analysts, researchers, founders etc.?

We also know that games are not reality. But can a well-constructed wargame be a useful approximation to reality? As we consider the transition of wargames to other industries we must think about the notion of play-acting. In business school we took classes where we were asked to participate in a business simulation—a computer game with controlled variables that changed the course of a product’s trajectory (from launch to success or failure) over a period of ten turns (the game’s version of a business quarter). The whole simulation was a highly simplified approximation of what it takes to launch and run a product and we could never quite shake off the feeling that we were merely playing, and not learning a thing. Rohit Krishnan’s comment on implementing a version of wargaming for business captures this feeling:

For wargaming to succeed as a solid initiative, it needs to be designed such that it doesn’t feel like play-acting. However, Danny Crichton makes a solid point:

“Open-ended play is just as useful for learning in adults as it is in children, and a stimulating scenario is infinitely more interesting and memorable than a dry report prepared in some basement dungeon of an office.”

After all, most exploration is like playing. We are searching for different solutions by trying out lots of different things, in this case by speaking and debating with lots of different players.

Wargaming and Grand Strategy

Here’s Danny and his team’s vision for their version of wargaming:

“That’s why we’re starting the Lux Riskgaming Initiative to help all kinds of leaders build up their expertise, risk-taking acumen and decision-making skills by confronting them with realistic but challenging scenarios on the frontiers of our collective understanding.”

— Feb 2023. Danny Crichton. “Lux Riskgaming Initiative”

Let’s break this vision down: the goals of this style of wargaming are to build a leader’s:

Expertise

Risk-taking acumen

Decision-making skills

We are reminded of a similar discipline that aims to achieve the exact same goals. The discipline of Grand Strategy.

The book that introduced us to the field of Grand Strategy was John Lewis Gaddis’s ‘On Grand Strategy’, which spun off from his teaching at Yale. In it, he defines Grand Strategy as the ‘alignment of potentially infinite aspirations with limited capabilities’. In a single sentence he captures what it means to have a strategy: in every field (business, warfare, diplomacy) we are met with constraints that limit our ability to achieve our goals. Whether it is gaining market share, getting more deals, finding talent, navigating supply chains to on-shore manufacturing—all these challenges are faced with material constraints that hamper them. Strategy is our ability to navigate through them.

Even though we are fans of Grand Strategy—we love its consilient nature2—we understand that there is a central dilemma. Most people studying this discipline are not in a position of power where their ‘grand strategic’ decisions matter. As former Bush administration foreign policy wonk Dov S. Zakheim puts it:

The politics of high policymaking is sexy, alluring, and magnetic to journalists and others outside government. The politics of implementation, of translating intentions into reality, on the other hand, is hard for those without government experience to grasp without some technical knowledge, analogous personal experience, a willingness to account for the views of others whether elsewhere in government or other governments, and a willingness to modify or even abandon preconceived notions that clash with harsh reality.

—A Vulcan's Tale: How the Bush Administration Mismanaged the Reconstruction of Afghanistan

So in order to be considered ‘good’ at the craft of Grand Strategy, we need to have a certain domain expertise, personal experience, and an ability to collaborate with others. Some of these skills will undoubtedly take years to master.

Plus, Grand Strategy has historically been ‘grand’. Like the Kriegsspiel of Prussian princes, it was the domain of an elite class of people. As Tanner Greer points out: “the protagonists of grand strategy are the grand men—presidents, supreme generals, and kings”3. Can it be studied now by aspiring leaders? Can elements of wargaming make grand strategy more accessible to a wider group of people and give them the tools of greater analysis?

In the past, I have made no secret of my disdain for Chef Gusteau's famous motto: "Anyone can cook." But I realize, only now do I truly understand what he meant. Not everyone can become a great artist, but a great artist can come from anywhere.

— Anton Ego, from Pixar's ‘Ratatouille’

Subjects like Grand Strategy can often seem like the domain of the elite, but its best practitioners were people of modest backgrounds, who had to work their way towards influence to deploy their vision.

One such practitioner was George F. Kennan.

The year was 1946. A disillusioned George F. Kennan was contemplating resigning from the Foreign Service of the United States. Hailing originally from modest Milwaukee, Kennan had spent the last twenty years of his life in the Foreign Service, and in the last two years he had been Ambassador Averell Harriman's deputy chief of mission in Moscow. Even though Kennan had just an undergrad degree (something that could have barely prepared him for the tumultuous years ahead), he was a staunch observer of Russian affairs, and spent years learning their language, literature, history and culture, while liaising with officials from both countries.

Yet his power was limited.

His objections to his fellow diplomat’s smoothing over of Russia’s totalitarian tendencies were not listened to. Kennan had an image of what a Foreign Service member should aspire to—in a letter to his friend Charles Thayer he wrote that these people should be “scholars as well as gentlemen, [and] who will be able to wield the pen as skillfully as the teacup”—and his fellow members were not making the cut.

So he took matters in his own hands.

In February 1946, Kennan authored a lengthy analysis commonly called the Long Telegram and cabled it from Moscow to Washington. The telegram (the longest ever written) was a wide-ranging essay about the methods and motives of Soviet communism and the potential ways the United States should respond. The strength of the memo found a receptive audience in Washington and Kennan would later recall that after this he was no longer shunned, and his ‘voice now carried’. His strategy of ‘containment’ would become the dominant American foreign policy in the Cold War era.

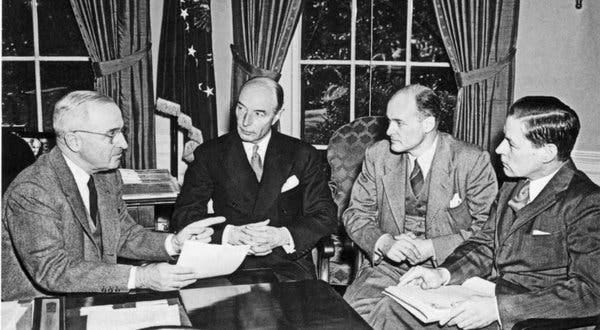

Kennan’s deep study and astute analysis made him a perfect practitioner of Grand Strategy, even though he originally didn’t have the ears of the power-brokers in Washington. Even though history now sees him as part of the Establishment—the so-called Wise-men4, he was in many ways an outsider figuring things out. It is these people who end up making making the most impact, and not the so-called ‘big thinkers’ (so prevalent in Grand Strategy circles) who don’t actually know what it’s like to do the hard work of execution. A ‘high-minded indifference to practicality’5 just doesn’t work in a rapidly shifting world.

Training Grand Strategic Ecologists

One thing is clear: Grand Strategy is an ecological discipline—one that requires the ability “to see how all of the parts of a problem relate to one another, and therefore to the whole thing”6.

This requires explicit training.

We believe practise in wargames and training in the classics can create leaders in the consilient tradition of George Kennan. John Lewis Gaddis and his partners at Yale believed this too.

Maybe we can learn from their playbook. The structure of the original Yale Grand Strategy course taught by Professor Gaddis, and his colleagues Charles Hill and Paul Kennedy was divided into three semesters with each semester covering a distinct ‘school’:

The School of the Classics

The School of Surprise

The School of Responsibility

At Mortimus we’ve read in depth about this program because we have always wanted to learn this discipline from its best teachers. Sadly, we never got the chance to take this course, but we can always reverse-engineer it and apply it to our own self-guided curriculums.

In the School of the Classics students read the classics of strategy: “Thucydides and Kennan ... Sun Tzu, Polybius, Machiavelli, Elizabeth I, Philip II, the Founding Fathers, Kant, Metternich, Clausewitz, Lincoln, Bismarck, Salisbury, Wilson, Churchill, the two Roosevelts, Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mao, Kissinger, Isaiah Berlin, Ronald Reagan.”

Thinking beyond just history and statecraft, we can modify this section to include readings from other disciplines as well. After all, some of the questions that Danny poses: “How will synthetic biology and the CRISPR economy change the organization of American healthcare? How do public schools compete with the prevalence of homeschooling in an era of social distrust? How will emerging markets compete in industries that require large capital outlays like semiconductors?” are also strategy questions. And so maybe it’s worth reading Carlota Perez’s “Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital”, Clayton Christensen’s “The Innovator’s Dilemma”, Geoffrey Moore’s “Crossing the Chasm” or any of Michael Porter’s works on the competitive dynamics of companies and nations.

The School of Surprise and the School of Responsibility was where students put their theory to practise. Gaddis and team modelled it after an Odyssey, where ancient heroes pitted their strength and learning against the monsters of the real world. Students would have field assignments where they would be in locales of interest (think Ukraine, Israel, Red Sea today) and gather notes, and in the latter half of the class they would go through a bootcamp of policy briefs and crisis simulations.

In reality, what it boiled down to was Field Research.

John Le Carré said a ‘desk is a dangerous place to view the world’. We agree. So does one of our favourite investors Alix Pasquet, who outlined what field research could look like for budding investors in a talk he gave at Columbia Business School. Field research is essentially on-the-ground knowledge. For businesses: it’s first person knowledge and experience of the business’s interactions with its customers, suppliers, competitors, and geographies. For international relations it is speaking to different stakeholders, policy makers, knowledge experts. It’s a matter of human collaboration.

Wargaming can be a non-costly way to recreate this element of Field Research, granted that diverse experts can be brought to the gaming table. It’s like a competitive, dynamic, socratic discussion on real-life issues. Lux’s first publicly available riskgaming scenario is Hampton at the Cross-Roads which imagines a hurricane paralyzing crucial U.S. naval assets and facilities in Virginia, and the potential fallout faced by local government, representatives of the federal government, CEOs, union presidents and the defence establishment. A perfect scenario for Lux’s audience of people at the intersection of science, business and policy.

We would love to see more games (and hopefully participate in some) which involve even more interesting situations. What would the rise of GLP-1 drugs (like Ozempic) have on sleep apnea companies? On the sale of obesity-adjacent drugs? Wargaming can be an apt way to ‘game-out’ macro trends, and can be a valuable tool for young analysts to work alongside experts—analogous to the ‘pair-programming’ paradigm in software engineering.

With students of varying disciplines coming together, or analysts of multiple sectors joining in and sharing their individual knowledge about an industry—this could be a fantastic avenue of learning and gaining expertise.

All of this to say—we’re excited about the future of Lux’s riskgaming, and all its potential offshoots.

Onwards to Consilience!

For a wonderful guide to the history of Wargaming, see the big tome: On Wargaming: How Wargames Have Shaped History and How They May Shape the Future, by Matthew B. Caffrey Jr.

The field navigates the seas of history, psychology, literature, game-theory, geography among others.

The term refers to Averell Harriman, the freewheeling diplomat and Roosevelt’s special envoy to Churchill and Stalin; Dean Acheson, the secretary of state; George Kennan, self-cast outsider; Robert Lovett, assistant secretary of war, undersecretary of state, and secretary of defense throughout the years of the Cold War; John McCloy, one of America’s most influential private citizens; and Charles Bohlen, diplomat and ambassador to the Soviet Union. Their exploits were documented by Walter Isaacson and Evan Thomas in “The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made”.

Dov Zakheim, A Vulcan’s Tale: How the Bush Administration Mismanaged the War in Afghanistan (Washington DC: Brookings, 2011), 294.

“What is Grand Strategy?”, John Lewis Gaddis