Cybernetic Industrial Chic

An exploration of futuristic images, words and us.

Sometimes essays should be short and sweet. We’re experimenting with a new style of essay for the next few months, one that is light and meandering in its scope. This series will act as breadcrumbs for future, longer pieces.

The Visionary

WHAT IS MR. HUGO possibly thinking about?

Sitting on a chair at his desk as he straps on what looks like a radio (with two antennae, my god), Mr. Hugo Gernsback looks wackier than ever. What is going on in his mind? What sci-fi dreams is he coming up with?

Hugo Gernsback. I had never heard that name until quite recently, and it’s strange because one of science fiction’s top prize, The Hugo Award is actually named after him. Here he’s being photographed by renowned American photojournalist Alfred Eisenstaedt1 for LIFE magazine, while he demonstrates his “teleyeglasses” — a kind of portable TV set. As the Apple Vision Pro hits the market, it would be remiss not to think of Mr. Gernsback who was one of the earliest influencers of the VR-age.

We at Mortimus love Mr. Gernsback, not only because he was an old-school consilient person (he was a writer, editor, inventor, engineer) but also because he was wacky (I think the bowtie gives it away — or the ‘Death Mask of Nikola Tesla’ in the background).

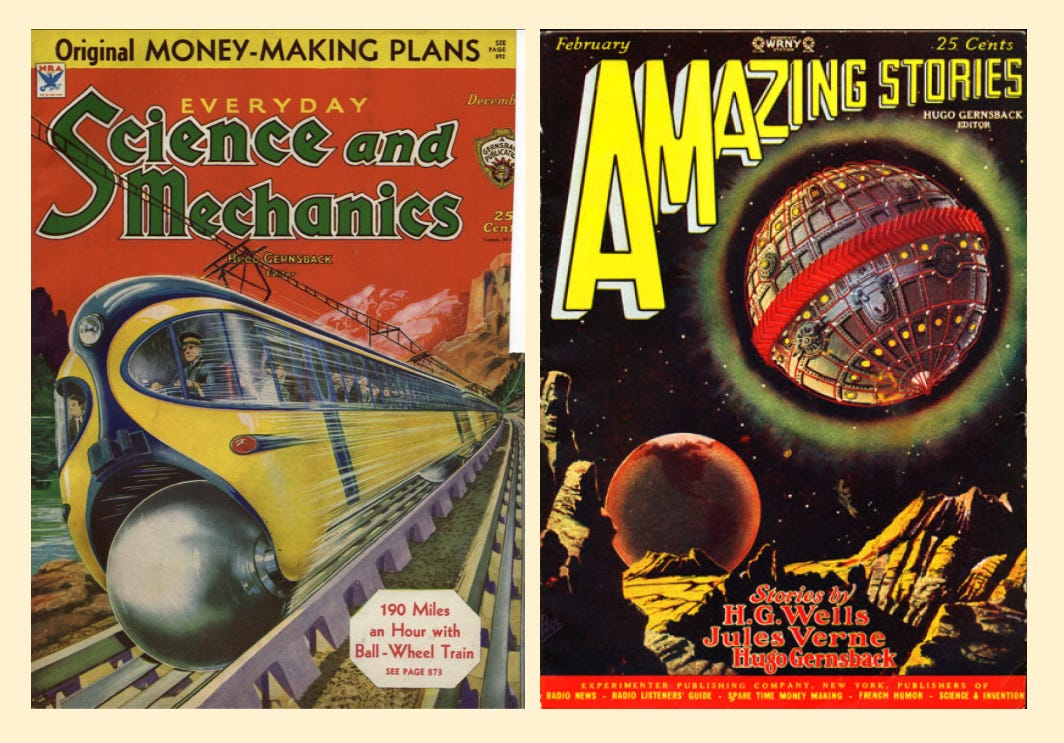

Among peers like H.G. Wells and Jules Verne, Hugo is considered as one of the ‘Fathers of Science Fiction’. While working for an electronics import-export company, he founded Modern Electrics, which in 1908 was the world’s first magazine about electronics and radio. Apparently the magazine bug caught him, because for the next few decades he’d stay in the magazine business and eventually launch two fantastic magazines — Everyday Science and Mechanics (which dealt with the science of today) and Amazing Stories (which dealt with the science of tomorrow).

It is here that our story begins. The visions that Hugo Gernsback unleashed upon the world are beautiful, strange, bizarre and wacky. Since the publication of the first issue of Amazing Stories, he opened a faucet and a rushing stream of imaginative futures came out, inundating the public consciousness.

The Gernsback Continuum

The purpose of a thought-experiment, as the term was used by Schrödinger and other physicists, is not to predict the future—indeed Schrödinger’s most famous thought-experiment goes to show that the “future,” on the quantum level, *cannot* be predicted—but to describe reality, the present world.

Science fiction is not predictive; it is descriptive.

— Ursula K. Le Guin2

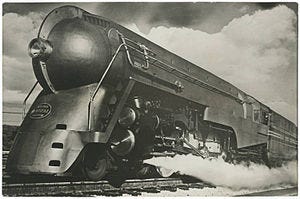

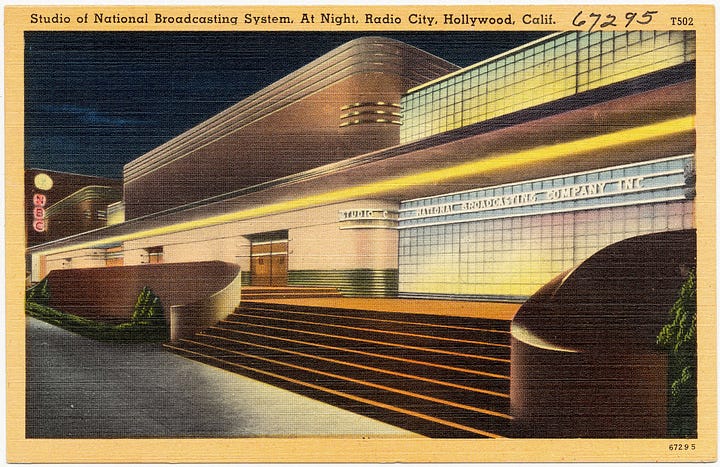

The images that sprang from the sci-fi future of Mr. Gernsback have had many names throughout the years. Many artistic schools blend together in this era: Art Deco, Streamline Moderne, Futurism, Raygun Gothic3, and Space Age.

Based on the material possessions of their society at the time, writers, artists, and architects envisioned worlds of the future. A dreamworld of streamlined chrome-shells, zip lines of speed, curving forms, long horizontal lines and a spattering of nautical elements.

It was a unique style, a sort of cybernetic industrial chic.

Why Cybernetic? Because it existed in a loop. The field of Cybernetics is obsessed with studying circular causal systems whose outputs are also inputs. You can apply the same logic to these visions — they sprang from the creative’s vision of what the world ought to be, which shaped architecture, art, illustrations, and which in turn shaped the visions again. A self-reinforcing feedback mechanism.

What’s strange is that this style somehow fell out of favour sometime after the 60s. The end of the Space Age signalled an aesthetic decline in the kind of art and architecture that would be at home in the world of the Jetsons.

Maybe this style had a “kind of sinister, totalitarian dignity” to it4. Or simply, tastes changed. Regardless, remnants of this style now merely dot the broken roads of America, in its gas stations, motels, spartan buildings. Or in the case of L.A., stuck in the middle of a parking lot:

Somewhere along the way, this aesthetic-chain of futuristic visions that birthed ‘Cybernetic Industrial Chic’ broke apart. I often wonder what happened to the remnants of those visions, the orphaned children of an idealized utopia.

In her introduction to The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula Le Guin wrote that science fiction is not predictive, it is descriptive. The Space Age aesthetic of these artists wasn’t a prediction of the future. It was a collective yearning of generations manifested into material things. It was descriptive of their current state. People didn’t care for the constraints of fossil fuels, foreign wars, geopolitics. They wanted to imagine a perfect society — and to eventually live in one.

But there is no such thing as a perfect society. It is the messiness of our lives that makes us human.

The New Gods

But our society, being troubled and bewildered, seeking guidance, sometimes puts an entirely mistaken trust in its artists, using them as prophets and futurologists.

— Ursula K. Le Guin

I’d like to think that our attempts to create these futures are merely attempts to gain control.

That is why the phrase Cybernetic Industrial Chic is useful. The clearest enunciation of the concept of cybernetics comes from Peter M. Asaro5:

The basic idea of Cybernetics is that complex systems–such as living organisms, societies and brains–are self-regulated by the feedback of information. By systematically analyzing the feedback mechanisms which regulate complex systems, cybernetics hopes to discover the means of controlling these systems technologically, and to develop the capability of synthesizing artificial systems with similar capacities.

So whereas there’s nothing wrong with visions of a streamlined future, there’s always a sinister undertone to them.

Lately, the orphaned children of the old Space Age era are coming back. I’ve seen it happen — AI hype is creating its own Industrial Chic.

The next few years are undoubtedly the years of AI. Everyone’s talking about it, it’s on everyone’s mind at Davos6. Whereas the believers and builders are focused on the beneficial aspects of it (and there are many), we cannot extricate it’s ability to control and shape us. Remember the reflexive power of images: they shape us and in turn we shape them.

But here’s the problem. I can’t help but be mainlined these visions.

Tomorrowland is the best drug there is.

He’s the photographer most well known for this famous photograph of the V-day kiss at Times Square.

All of Ursula’s quotes in this essay are from her Introduction to The Left Hand of Darkness.

This term was coined by William Gibson in his short story ‘The Gernsback Continuum’ which is the title of this section, and the inspiration for the essay.

See above, William Gibson, ‘The Gernsback Continuum’.

Peter M. Asaro, “What Ever Happened to Cybernetics?”

Cybernetics once again! The top-down nature of Davos (it is a summit after all) is a signal that control of AI is on a lot of world leaders minds.